Bingham High School During World War I

BINGHAM HIGH SCHOOL DURING WORLD WAR I

(Third in a series of stories of Bingham High School 100 years ago)

by Scott Crump

Many of us living in 2021 look at all the events happening around us, whether it be the COVID-19 Pandemic, record unemployment, an economic downturn, horrific wildfires, race riots, the attack on the US Capitol or a poison political environment and think to ourselves that things could not be worse. Fortunately, history gives us some perspective to know that Bingham Miners 100 years ago may have thought the same thing. At that time the world was involved in World War I (1914-1918) and the global Spanish Flu Epidemic (1918-1920) as well as the tragic economic, political and social aftermath of those events. It is estimated that 50 million people worldwide (675,000 in the US) died in the Spanish Flu Epidemic and there were over 20 million deaths in World War I. (By comparison, the global coronavirus pandemic by March 2021 had caused over 500,000 deaths in the US.)

In March 2020, I wrote about the flu epidemic at Bingham High School, which like the Coronavirus Pandemic today had a major impact on the Bingham Community, and in October 2020, I wrote about a tragic love triangle at Bingham High in 1917 (see the Bingham Alumni Facebook page, the Bingham Alumni Website www.binghamalumni.org or Scott Crump’s book Bingham High School—The First Hundred Years (1908-2008)). This article will talk about Bingham High School’s involvement in World War I.

WORLD WAR I

Although World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, the United States was not involved until 1917 when President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war. As the cauldron of war boiled over and engulfed the United States, Bingham High prepared for the fight and welcomed new principal, Lars W. Nielsen (1917-1924). Preparations for war began as early as the spring of 1917 when Jordan District Superintendent Orson Ryan attended a meeting with the state superintendent to determine what the schools could do to help the war effort. A state resolution was passed stating schools were ready to assist the government and country in every way possible, but that it was not yet necessary to close schools. If conditions arose that made it necessary, however, the superintendents would be ready to do so. Another resolution provided that students who enlisted for military service or who were required to remain out of school to work, would be excused from school without losing credit. Interschool athletic events were discontinued for the year, and principals were encouraged to implement physical exercises within the schools instead of competitive sports. (117)

A number of Bingham’s young men joined the armed forces and were sent to fight in Europe. The town of Bingham was overrun with military recruiters. Store windows and utility poles were covered with signs reading, “Uncle Sam Needs You.” Eight Bingham High Students are pictured in the 1918 yearbook as having answered their country’s call to duty. Bingham English teacher, Inez Todd King, wrote the following in 1918 as some of her students went off to war:

A year ago, some of the boys of the class of 1917 responded to the nation’s call for men. We walked with them to the depot to tell them “God speed.” As I looked into their faces, my thoughts went back over the time I had known them. It did not seem possible that these calm, quiet men were the boys who but yesterday had been eagerly looking for some new prank with which to astonish their fellows. They stood there, shoulders square, heads up, eyes bright, the spirit of the (mining) camp, made flesh and blood.

Beside them stood the boys and girls who had been playmates and companions in the childhood which had vanished forever. In their faces was no sign of hysteria. Each wore a smile—a little tremulous perhaps –but nevertheless courageous. The Class of 1917 sent its forces away with a smile, and so man and woman, it won its first great battle of life – the fight for self-control and self-forgetfulness.

God bless them all. They are splendid representatives of the camp, active, fearless and loyal, endowed with spirit of youth, and the self-control which the majesty of the mountains which surround Bingham, gives to all the people who lift their eyes to the white peaks. (118)

Programs instituted to conserve food and natural resources urged Binghamites to observe “Wheatless Mondays and Wednesdays,” “Meatless Tuesdays,” “Pork less Saturdays,” and to abstain from meat for one meal a day. Sugar was restricted and removed from restaurant tables. Adding to these efforts, the girls in the Bingham Domestic Science and Arts classes were taught lessons in food conservation, budgeting, and economical planning and serving of war menus. (119) Many students in the Jordan School District (mostly in the valley) made an important contribution to the war by raising and harvesting farm crops, especially the sugar beets. In 1917, Dr. Daniel C. Jensen, Jordan School District’s superintendent, adjusted the school calendar by starting school one week early and extending it one week later to accommodate a two-week fall vacation during the beet harvest. This allowed farmers to take advantage of students’ help without anyone missing school. (120)

The fabled Jordan District beet vacation began October 15, 1917. Students in the grammar grades (5-8) and at Jordan High School were dismissed to work in the beet fields. Students in the primary grades (1-4) and those living in Bingham remained on a regular school schedule. (However, Bingham High School students were included in the beet harvests of the early 1940s due to the severe labor shortages caused by World War II.)

During World War I, there was a constant need to conserve fuel and to raise funds for numerous war-related causes. Government restrictions prohibited coal companies from selling anyone more than a month’s supply of coal. Schools were instructed to carefully watch their coal consumption in order to avoid having to close down before the end of the month due to the lack of fuel. In addition, all schools were encouraged to participate in Red Cross and Liberty Bond drives. In December 1917, schools throughout the District were closed for a half day to allow students to solicit Red Cross memberships. The leaders of the drive reported to the Board that more than 2,900 memberships had been secured in the Jordan School District as a result of the children’s endeavors. The Bingham City alone subscribed nearly $400,000 to the Liberty Loan Drive. (121)

Binghamites, with few exceptions, embraced the war effort and there were rivalries between various civic organizations as to which one could be the most patriotic. A large American flag was raised over the Denver and Rio Grande railroad yards, and flag raising ceremonies were held throughout the community. Governor Simon Bamberger addressed a patriotic gathering in Highland Boy on the subject of “Our Foreign Population” with music provided in part by some girls from the high school, the Carr Fork Band, and A. W. Lubeck’s Band. The most visible sign of community support was a large patriotic banner stretched across Main Street in front of the Bingham Mercantile that remained until the end of the war. (122)

With patriotism and anti-German feelings running high during the war years, the School Board authorized flag poles to be constructed at all the buildings in the Jordan District and copies of the pamphlet, History of the Flag, to be purchased and distributed to each school. In April 1918, the board even passed a resolution requiring the District to discontinue the teaching of the German language and any German ideas. (123)

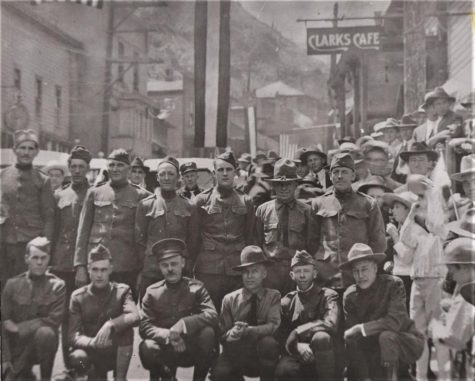

On Monday November 11, 1918, the news of Germany’s surrender reached Bingham touching off a celebration unsurpassed in the town’s history. Mayor Q. B. Kelly issued the official armistice proclamation, and Police Chief A. E. Pantsh “threw open the town” inviting all residents to enjoy themselves in the full spirit of the occasion. Mining companies gave their employees a half day off, businesses closed their doors, and school dismissed for the rest of the day. The Bingham Bulletin described the celebration as follows:

The town was soon crowded with people all in the happiest mood. It has been a long time since such a large and good-humored crowd has been in the old camp. Everyone was happy, the crowds marched through the canyon cheering the occasion, great flags of America and the allied nations were floating from all automobiles which entered and departed from the camp.

As night came on and the crowds became more and more jubilant, the occasion was further enlivened by some of the best music ever heard in Bingham… (124)